How to Solve Your Unstructured Data Problem

Unstructured data is information that’s difficult for software systems to store, search, or analyze.

It’s the kind of data you won’t find in a fixed, predefined format. It won’t fit neatly into a spreadsheet’s rows and columns. It might be a handwritten note in the margins of a form, an email chain, or even feedback on a social media platform.

None of that is difficult for humans to parse, because we understand meaning from context, but software systems have traditionally required explicit structure to interpret information. It’s why issues like data portability (transferring data between different systems) remain so challenging to solve.

Imagine a doctor writes a note that says, “Start metoprolol 25 mg bid.” A human expert would understand that means “begin taking 25 milligrams of metoprolol twice a day.”

But to an electronic health record (EHR) system that accepts specific key-value pairs, it’s meaningless. A human would need to “clean” and format the data. Perhaps something like:

{

"medication": "metoprolol",

"dosage": "25mg",

"timing": {

"repeat": {

"frequency": 2,

"period": 1,

"periodUnit": "d"

}

...

}This becomes a problem at scale because unstructured data is 80% of all healthcare data.

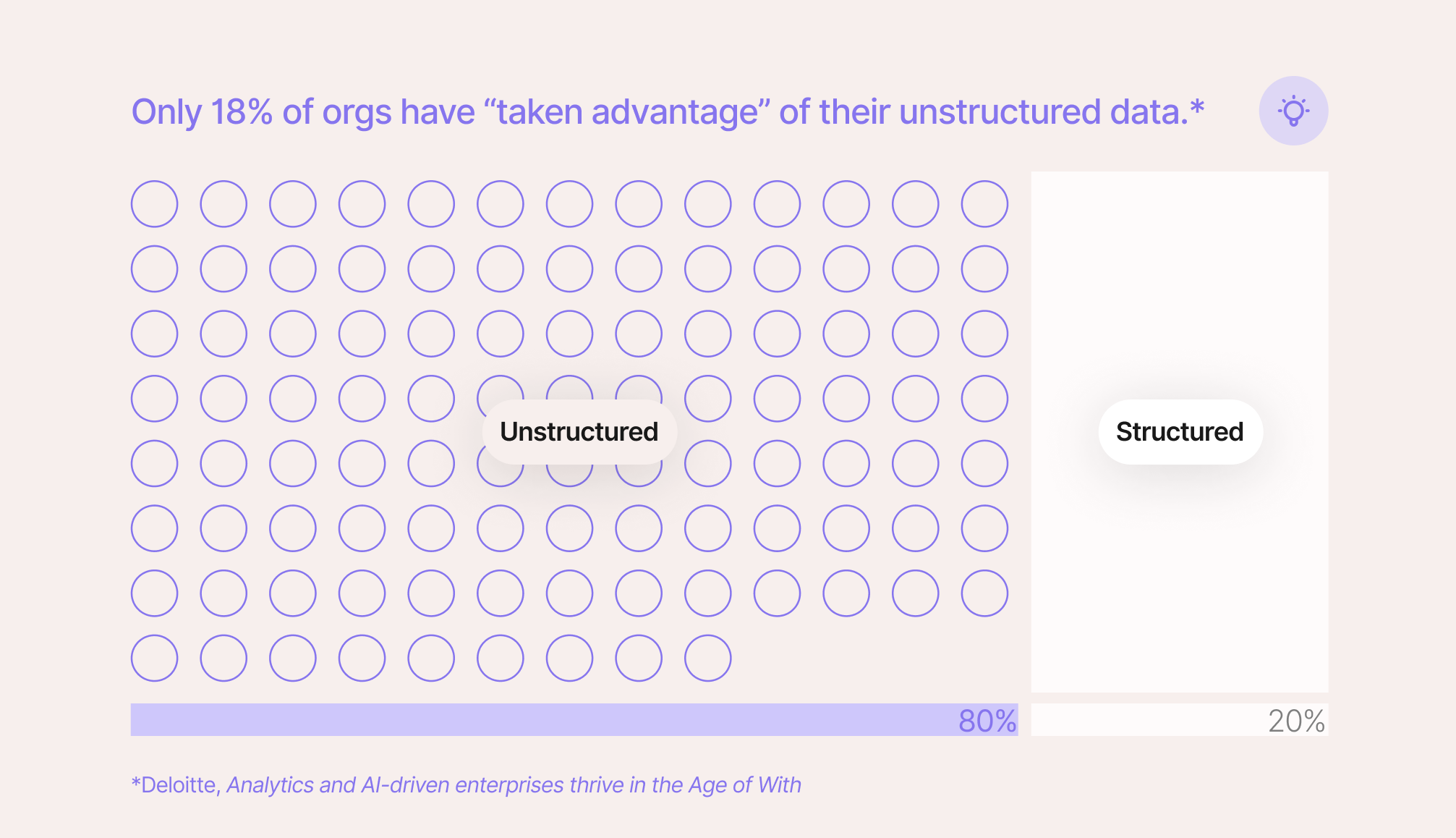

And only about one in five organizations claims to be using unstructured data systematically.

Unsurprisingly, those organizations are more successful than the rest. Executives who call unstructured data a key source of valuable insights “are 24% more likely” to beat their operational goals, according to Deloitte.

For everyone else, they’re… just not using 80% of their total data volume.

Of course, there’s a reason so few organizations take advantage of all that data. It’s hard to take advantage of. Humans usually don’t have time to sift through it all, and most software isn’t smart enough to figure it out on its own.

Making Unstructured Data Actually Usable

Simply digitizing, say, a clinical note as part of a downstream workflow doesn’t make it useful. Digitization isn’t equivalent to “usability.” Usability requires structure, context, normalization, and implementation.

That requires real-time natural language processing (NLP), patient data stored in integrated management systems, and complex data models to make sense of it all.

And, of course, a human pilot, someone to spot check and handle the edge cases.

So, over the last five years, we’ve been collaborating with lab managers, retail pharmacists, and healthcare administrators to build a solution to do all of that: DocKnow.

DocKnow is an intelligent document processing platform built specifically for healthcare and life sciences. DocKnow’s AI has been trained on thousands of healthcare documents, includes out-of-the-box integrations with ICD and CPT taxonomies, and is designed with No-Data Architecture to ensure no PII, PHI, or any other sensitive data is accessible to Onymos.

Below, you’ll see how DocKnow uses techniques like semantic reasoning and named entity recognition (NER) to find a missing form field value (“Last Name”) in unstructured data:

What DocKnow Did Step-By-Step:

Step 1: Named entity recognition (NER)

The NER model scans the document and identifies potential person names. It recognizes “Madeline Johnson” as a person entity based on capitalization (e.g., both words are capitalized), their position in context, and common name patterns learned during initial model training.

Step 2: Document structure understanding

The model recognizes the document type based on its header, the presence of subheaders like “REASON FOR VISIT,” and its overall formatting and language. It understands that, since this document is bundled with this particular form, “PATIENT: MADELINE” is likely a reference to the “First Name” field value “Madeline” under “PATIENT INFORMATION” in the primary document.

Step 3: Corroborating evidence

DocKnow then validates this logic by looking for corroboration. Later in the note, the full name “Madeline Johnson” appears again in the same order in the phrase “New patient, Madeline Johnson, referred for consultation…” confirming its parse. An MRN field is also present, indicating we’re referring to a specific patient.

Finally, there’s no contradictory information suggesting a different name altogether (though, if there were, DocKnow would highlight both names for a human-in-the-loop reviewer).

Step 4: Confidence scoring

The system assigns a confidence score to this extraction based on:

- Multiple mentions of the name in a consistent format (HIGH confidence signal)

- Clear document structure with a labeled patient field (HIGH confidence signal)

- Common, recognizable name components (MEDIUM-HIGH confidence signal)

- No ambiguity or conflicting information (HIGH confidence signal)

We might estimate a resulting confidence score of 95%+ that “Johnson” is Madeline’s last name.

Step 5: Field mapping (structuring the data)

DocKnow maps the extracted information to structured fields (JSON, by default):

{

"firstName": "Madeline",

"lastName": "Johnson",

"dateOfBirthMmddyyyy": "07/22/2010",

...

}To sum it up, DocKnow used contextual NER to identify the name, document structure understanding to know the name referred to the patient (not a doctor or family member), and confidence scoring to ensure accuracy.

It all worked together to extract “Johnson” from the unstructured text.

But this is just one use case, and my explanation still only scratches the surface (we didn’t talk about conformal predictions or adaptive confidence scores).

If incomplete forms, disconnected systems, or plain low-quality data are costing your organization time, money, and insight, you’re not alone, but you don’t have to stay stuck. DocKnow solves the unstructured data problems that keep healthcare organizations from reaching their operational goals. Reach out, and let’s talk about what’s possible when your data actually works for you.